Prof. Theriault: It is pointless to engage in dialogue unless Armenians can have equal footing with Turks

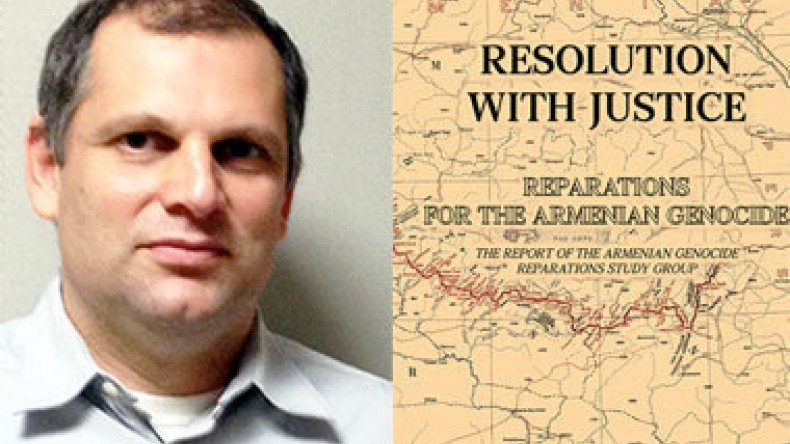

Nvard Chalikyan from Panorama.am has spoken with Professor Henry C. Theriault – Chair of the Armenian Genocide Reparations Study Group (AGRSG) about the recently published report of the Group titled Resolution with Justice: Reparations for the Armenian Genocide (Armenian and English versions of the executive summary and full report are available here.

Part 3

Nvard Chalikyan: Judging from your own experience, how would you say the Turks who recognize the Genocide approach the reparations issue?

Prof. Henry Theriault: The process typical Turkish people would have to go through to be able to talk about reparations may be very long and complex, given that their government and educational system obviously are doing everything to prevent that. But I can say I have had the good fortune in the last five years to connect with a number of Turks working on these issues and they completely understand that reparations are central for dealing with the Genocide. For instance, I just gave a talk as part of the Hrant Dink commemoration in Ankara in January 2015 and reparations were on the agenda. Even in 2010 when I was in Ankara at a big conference on Armenian Genocide held there, I was stunned by how openly many of the Turkish speakers were discussing reparations, treating it as a fundamental issue.

Of course, there are other Turks who recognize the Genocide or at least that there was harm done to Armenians in 1915, if they won’t use the correct term, and who stop there. On the one hand, I can understand. After all, just recognizing the Genocide, even without the term, can provoke negative reactions, even legal prosecution, in Turkey. At the same time, it seems that recognition of the Genocide in a true sense means not just recognizing the historical facts but their wrongness and, thus, the obligation that wrongness entails for today’s Turkey. Accepting the need for reparations is, really, part of genuine recognition of the Genocide.

While perhaps some of these Turks might say that reparations could possibly be discussed later, but doing so now will just alienate Turks, I disagree. I believe that holding back from discussing an issue in its full sense prevents progress on the issue. Martin Luther King did not spend his days as a leader asking for better segregated schools for blacks or some half-way measure like that. Even though much of white America absolutely did not want to hear that segregation should be ended completely and blacks’ full equality recognized, Dr. King made this clear again and again. This pushed whites to rethink their positions, instead of allowing people to avoid the hard issues. Similarly, average Turks need to be exposed to the issue of the Genocide in its fullest light, not some easy, reduced version that will make them feel comfortable. Serious engagement with genocide is never comfortable.

I believe there is a significant number of Turks who have an internal conflict between a genuine sense of morality – they want to do right by Armenians – and the impact of nationalist forces on their psychology and individual identity. This impact is strong, and makes it psychologically difficult to question the official version of Turkish nationalist history. As long as such individuals are presented with unchallenging approaches to the Genocide and not pushed to a level of discomfort, they can balance these conflicting psychological demands. It is pushing the issue that can help them finally tip the balance in favor of good ethical principles . . . trend that can also free them up to rethink and reconfigure Turkish identity in positive new ways.

N. C: What percent of Turkish scholars and activists who recognize the Genocide do you think accepts that Turkey should pay reparations, and what percent of them would consider land reparations acceptable?

H. Theriault: The issue of group territorial claims is quite complicated – the percent of those who would accept group land reparations is extremely low. There is small but higher percentage for substantial material reparations, including return of individual or community properties such as churches to their owners but retention within the Turkish state. I believe that overall the number who accept material reparations is steadily increasing.

As this and my answer to the previous question suggest, there is a distinction between those scholars who are actually dealing with the issue (and use the word “genocide” in public) and those so-called “progressives” who are very soft on the issue. The latter avoid hard questions and often try to resolve their sense of what is right with not displeasing the powers that be. I’m not sure this balancing act is possible. In Turkey Baskin Oran is a good example of this.

There seems to be a growing debate between the stronger scholars in Turkey I have worked with and so-called “progressives” who aren’t dealing responsibly with the question. As the former push the issue, there does seem to be a trend toward a real discussion in Turkey not just about acknowledging something in 1915 but how this should be done with meaning.

N. C: Doesn’t the Turkish government use these “progressives” to control the discussion on the issue? Is there an agenda?

H. Theriault: I am not an expert on the details of the internal political dynamics of Turkey, but there is certainly an agenda on the part of the government; they are trying to play a very careful game by appearing to be open, but keeping things under control and not allowing them to get beyond a certain limit. For instance, there is another Turkish scholar, Halil Berktay, a sort of “progressive” scholar whom I have written critically about. His treatment of the Armenian issue appears to be imperialistic, even though he is supposed to be progressive, possibly even a Marxist, and all of that. It is interesting that he is becoming one of the leaders on this issue; the government seems to be working with him at some level and he seems to be an important voice in relation to the Turkish government’s efforts to deal with the Genocide. It’s obvious that they are picking that kind of scholar or activist over those whose engagement with the legacy of Genocide is more open and positive.

N. C: In your view what risks does the Armenian-Turkish dialogue have for Armenians?

H. Theriault: To put it in very simple terms, any dialogue initiatives have been meant to prevent frank discussion about recognition of the Genocide, let alone reparations. If that is the goal of the dialogue, then it is both pointless and insulting for Armenians to engage in it. Even some apparently well-intentioned Turks seem interested in having a dialogue simply to feel good about themselves morally; they want Armenians to like them, but they don’t want to admit what happened.

There is another important point to note. Conflict resolution models treat dialogue between a victim group and a perpetrator group as if they were equal in power. This is incredibly dangerous. The problem is that Turkey has the power while the Armenians don’t have the power, and when they engage in a dialogue they are in a very uneven relationship. Unless there is a mechanism to give Armenians equal footing with Turks, it is pointless to engage in that kind of dialogue. I think the Republic of Armenia probably needs to do a better job of using international law and international public relations to get itself support for balancing the power issue in dealing with Turkey.

That said, if the power imbalance and problematic agendas can be addressed, dialogue can be very productive. The Report addresses the question of dialogue by proposing the idea of Armenian Genocide Truth and Rectification Commission (AGTRC) designed to give a real alternative to a sort of false dialogue just discussed, of which perhaps the Turkish-Armenian Reconciliation Commission (TARC) is the best-known example. There are many people in Turkey who understand that there is a human rights issue they need to deal with. With these people Armenians should talk on a societal level.

That doesn’t mean that they all need to agree; they just need to have a common framework of respect for human rights and acknowledgement of the history of the Genocide to open the possibility of moving forward. The AGTRC could be the mechanism for providing opportunities for this kind of productive dialogue. We consider it, in fact, the best route toward a productive inter-group relationship with dialogue that can actually transform Turkish society away from its legacy of genocide and the various ways in which genocidal elements remain present within its institutions, social practices, etc.

N. C: What is the role of the Republic of Armenia as a state in raising and pursuing the question of reparations internationally?

H. Theriault: It would be very helpful if Armenia could develop legal and political cases internationally. It should of course also consolidate the support and expertise of the Diaspora in pursuing these cases – working together will create tremendous opportunities to change global public opinion. The US, Argentina, and other countries can also actually present legal cases to the ICJ or other appropriate courts, but obviously Armenia is the right state to take the lead on this. Otherwise, when Diasporans raise the issue in their countries it becomes very difficult to be taken seriously as people want to know why the Republic isn’t taking an advocacy role on this issue.

The question of whether and how to present the case in ICJ, European Court of Human Rights, or another avenue is a complicated one, as it can also backfire. For the Republic of Armenia it is now more important to pursue political advocacy. Armenia also needs to be working with other countries which are concerned about human rights issues and maintain the position that their willingness to support Armenia on this issue is an essential part of their relationship with the Republic. It is difficult to do that but it is really important. There are countries that the Republic can work with.

Interview by Nvard Chalikyan

Henry Theriault is Professor in and Chair of the Philosophy Department at Worcester State University in the United States. He has a Ph.D. in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts. His research focuses on reparations, victim-perpetrator relations, genocide denial, genocide prevention among other topics. He has published numerous journal articles and chapters in the area of genocide studies and given many lectures worldwide. Dr. Theriault is also a founding co-editor of the peer-reviewed Genocide Studies International and co-editor of Transaction Publishers Genocide: A Critical Bibliographic Review.

Newsfeed

Videos