In Armenia, art in the shadow of Ararat

RACHEL B. DOYLE for The New York Times

The show was about to begin at a Soviet-era playhouse with olive-green seats, antique Caucasian rugs and a tiled ceiling, in Yerevan, the Armenian capital. I was with a man almost 50 years my senior who, while giving me a tour of an experimental art center in a former disco that morning, had asked if I would join him at the State Theater of the Young Spectator that night.

Invitations like this are not uncommon in this country of 3.3 million, where tourists are still treated as guests to be invited home for coffee and sweets, or, as in this case, to be taken out to an avant-garde pantomime performance.

As the play began, it quickly became clear that this was nothing like the pantomimes put on for children in the West. This was a thrilling interpretive dance performance about a third-century martyr, St. Ardalion, his death suggested by the ribbon looped around his wrists and ankles. Ardalion had been hired to perform in a play that mocked Christianity, but he was inspired to convert onstage, and died for it instead.

The play aptly summed up Armenia, which is considered to be the first nation to adopt Christianity as its state religion, in A.D. 301, and which has persevered through the centuries despite being conquered by the Romans, the Persians, the Arabs, the Mongols, the Turks and, of course, the Soviets. It is a country that has not forgotten the Armenian genocide of the early 20th century, and whose national symbol, Mount Ararat, where many Christians believe Noah’s Ark landed, is now on the other side of the closed Turkish border.

Yet the play was also very much a product of contemporary Yerevan, where ancient traditions are juxtaposed with a vibrant arts scene and where a newly renovated airport is not far from several stunning cathedrals that date back more than a thousand years.

The creative energy is palpable: The city is filled with colorful stencils of famous writers spray-painted on buildings. A souvenir shop I wandered into had an abstract-painting gallery, Dalan Gallery, hidden away on the second floor, as well as five yellow and green parrots.

The Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art took over a cavernous Soviet-era dance club after the country gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and it now hosts about a dozen multimedia art exhibitions and festivals every year.

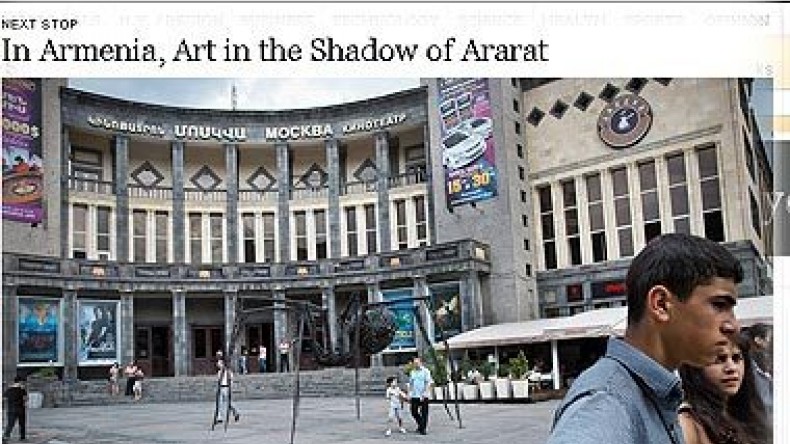

The first thing I noticed about Yerevan, speeding from the airport in a taxi at dawn, was that it was by no means a grayish post-Communist city. Buildings combine classic Soviet architecture with the striking pink and orange volcanic tuff rock native to the country. “Russians call it the pink city,” said Mane Tonoyan, a tour guide.

No personal connections had drawn me to this mountainous country. Brushes with the Armenian communities in Beirut and Istanbul had piqued my curiosity, but it was an urge to go somewhere that still felt like a secret, to explore a place most travelers knew little or nothing about, that led to my visit.

Indeed, despite offering a multitude of impressive historic sites, including a much older version of Stonehenge, called Karahunj, Armenia is barely on the radar of tourists, who visit neighboring Turkey in droves. That means that the services and accommodations set up for visitors can be rudimentary, though sometimes that just adds to its charm. On one tour I went on, the van driver suddenly stopped to chat and buy fresh eggs from a woman on the side of the road. After another excursion, a family of four invited me in to their apartment and plied me with strong coffee and traditional grape and walnut candy.

Armenia’s old monasteries and churches are perhaps its greatest cultural treasures and account for a number of Unesco World Heritage sites. One of the most intriguing monasteries is Geghard, a complex of churches and tombs carved into rocky cliffs 25 miles east of Yerevan, long known for housing the spear said to have pierced Christ on the cross. (The spear is now in a cathedral museum at Echmiadzin, west of Yerevan.)

I visited Geghard on my second day in the country. As I wound my way under the arches of the 800-year-old church’s candlelit stone chambers, I heard chanting growing louder and louder. Soon, I came upon a crowd gathered in an inner sanctum, and saw a monk in a black hood and a golden cape singing in a rich baritone, his voice echoing off the rock walls.

I must have looked a bit puzzled because just then a teenager in a lavender dress held her smartphone out to me. Using an Armenian-to-English dictionary, she had typed in the word for “baptism.” As a young boy clad in white stepped forward, I edged out of the red-curtained room so as not to intrude.

Outside in the square three musicians were playing the duduk, a traditional woodwind instrument made from the wood of an apricot tree; children were wandering about wearing crowns of flowers; sellers hawked white doves, to be set free after visitors made their wishes. On a platform off to the side, men in boots gutted a hanging lamb, its bright red blood spilling onto a stone; a woman in a head scarf told me they would give the meat to poor villagers. Save for the black-robed student monks texting on mobile phones nearby, the whole scene could have been a tableau from a thousand years ago.

That evening I watched a Franco-Russian violinist named Fédor Roudine, the grand prix winner of the Aram Khachaturian International Competition, performing concertos in an elegant 1930s concert hall. My ticket cost just 2,000 dram (or $5 at 400 dram to the dollar). When Mr. Roudine finished, two cannons on either side of the stage shot out bursts of glitter in red, blue and orange, the colors of the Armenian flag.

Like Mr. Khachaturian, the composer who was once denounced as “antipopular” and sent back to Armenia for “re-education,” the country’s artists often had to deal with government repression. The Soviets banned Sergei Parajanov, the legendary Armenian director, from making movies for 15 years after his critically acclaimed film, “The Color of Pomegranates,” was released in 1968.

To fill the void, Mr. Parajanov began to make collage art. Hundreds of his unique assemblages are collected in the Museum of Sergei Parajanov, an oddball standout of Yerevan’s rich house museum scene. One room is devoted to works Mr. Parajanov created during his nearly five years in prison, like bottle-cap carvings that look like old coins.

Despite the danger, Armenian intellectuals continued to test boundaries. During an era when “unofficial art” — anything besides Socialist Realism — was anathema to the Kremlin, and exhibitions of it were being bulldozed in Moscow, the authorities somehow allowed a modern art museum to open in Yerevan in 1972. “Even some artists didn’t believe it would open,” said Nune Avetisian, director of the Modern Art Museum of Yerevan.

The city’s Modern Art Museum was the first state institution of its kind in the Soviet Union. It is still hard to fathom how it was permitted to display works like Hakob Hakobyan’s “In a City,” a 1979 painting that shows a crowd of headless men raising handless arms in a Soviet-style square.

Perhaps the freedom the authorities allowed the museum was simply the result of the city’s geography: “It was so small and very far from the center in Moscow,” Ms. Avetisian said.

On my last day in town I traveled south to the Khor Virap monastery, passing deep gorges and endlessly rolling hills that seemed to touch the clouds, red-roofed houses and purple wildflowers sprouting from cracks in jagged volcanic rock walls. The snow-capped peak of Mount Ararat was always in the distance.

As I entered Khor Virap, where the main draw is a deep dungeon where Gregory the Illuminator, Armenia’s patron saint, was imprisoned in the third century, a young man brandished a large rooster at me, smiling mischievously. I had been keen to go to a country that still felt undiscovered, and while the rooster-seller might have guessed that the redheaded woman with a camera was not really in the market for a blood sacrifice, I appreciated the gesture.

Newsfeed

Videos