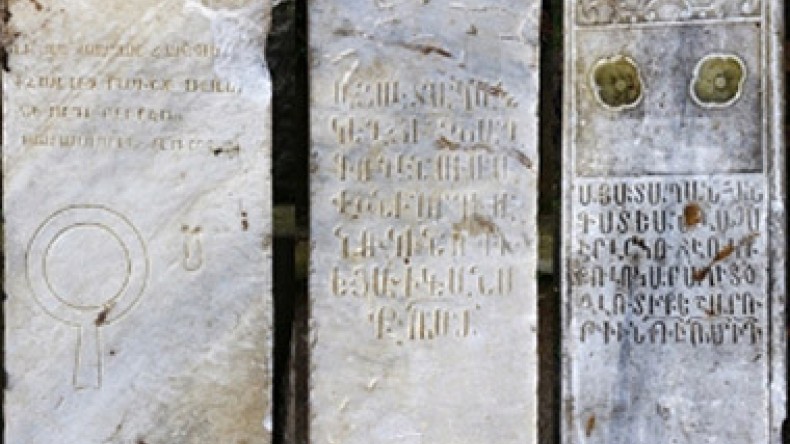

Armenian tombstones found in Taksim Square

The electronic version of the Turkish-Armenian weekly newspaper Agos published on Tuesday a list of Armenian names found to be inscribed on tombstones discovered in Taksim Square – the former site of an Armenian cemetery – during construction. The tombstones date to the 17th to 19th centuries, Asbarez reported, citing Armenpress.

The inscriptions that have been published are as follows:

Nikoghos, son of Martiros

Grigor, son of Yeghiazar

Dikesh Harutyun, son of Karapet, 1775

On return from St. Jerusalem, the wife of Ghazanchian Haji Tateos Agha, Haji Ann, reached God: May 23 1859

John Mikayeloghlu, son of Andiresli

Moses, son of Nerses, from Areveni Village, 1760

Manuk, son of Simavon, from Chomakh Village 1761

Barber Khachatur, son of Aslan, 1850

The tombstones are currently at the Istanbul Archeological Museum, the authorities of which are studying the stones. “The inscriptions on one of the tombstones are worn and illegible. The other two are without inscriptions. On five of the tombstones it is possible to read only the dates,” a museum spokesperson informed. The museum later reported that thirteen of the tombstones were found to be made of marble.

Widespread riots broke out in Turkey in May this year when the government announced its plans for replacing Taksim Square’s Gezi Park with a reconstruction of the historic Taksim Military Barracks and possibly a shopping mall.

While Taksim Square quickly became a symbol of resistance, liberty, and human rights for the young Turkish protestors, for an entire people it already represented something demolished a long time ago.

Unbeknownst to most of the protestors in Taksim Square, buried under their feet lies an Armenian past. Gezi Park was an Armenian cemetery before it was a park, the largest non-Muslim cemetery in Istanbul at its time. Legend tells that the cemetery was built at the order of Suleiman the Magnificent, when his imperial chef, Manuk Karaseferian, resisted a group of conspirators’ plans to poison the sultan’s food and instead revealed them. Asked what he would like for his reward, Karaserefian requested a place for Armenians to bury their loved ones.

This piece of Armenian life in Istanbul, as surreptitiously as all the others was buried under and forgotten in the 1930’s, after the Armenian Genocide. Now, as if still defiant a century on, ghosts of the past have returned with a haunting reminder.

The past is not lost on everyone, however. Every year, a Turkish human-rights group called DurDe organizes a silent commemoration on April 24th, when, in 1915, several hundred Armenian intellectuals were rounded up for execution. It intends to reinstall a memorial for the Armenian Genocide in Gezi Park, but pressure from nationalists has prevented this thus far. Cengiz Alğan, a member of DurDe, told Le Monde, “All the political parties are killing each other, but when it’s about Armenians, there is always a consensus.”

Newsfeed

Videos