Los Angeles Times: Dilijan Chamber reveals Tigran Mansurian's rebel side

Below we present an article by music critic Mark Swed, published in Los Angeles Times.

The stately, spiritual music of Tigran Mansurian has an underlying sadness. But the surfaces remain unflappable, surprisingly fleshy and incredibly beautiful. It is music that doesn't so much transcend suffering as absorb it, become one with it.

Luxuriant sensuality as spiritual balm is his secret weapon and no doubt what has made the Armenian composer, who turns 75 later this month, a stellar international figure.

Sunday afternoon, though, Dilijan Chamber Music divulged a different secret weapon during its Mansurian celebration at the Colburn School's Zipper Concert Hall. Underlying the sensuality and deeper even than the sadness is a feisty rebelliousness.

For a tribute concert, the program was a little strange. Of the six short Mansurian chamber works (all under 10 minutes), four were from his formative years as an Armenian living under Soviet rule. The other two were recent solos for clarinet and viola. There was little hint of the luminous large-scale scores of his maturity, on which his reputation rests.

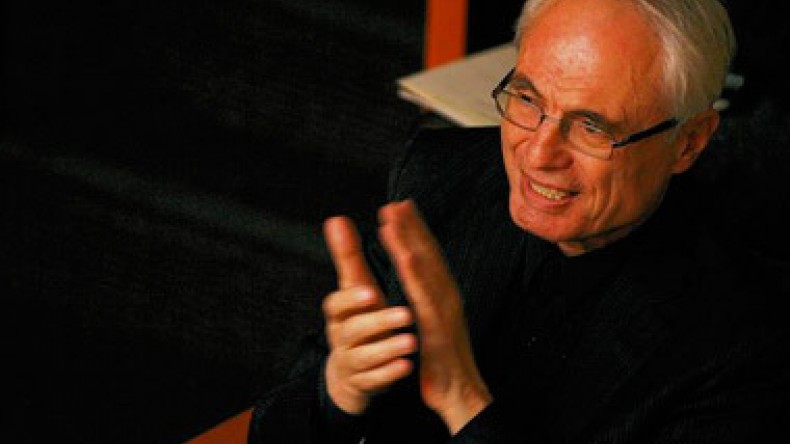

But given that Mansurian, who was on hand at Zipper and who clearly had a hand in selecting the program, has been a guiding force in Dilijan from the beginning, this was the intention. In remarks from the stage, Dilijan music director Movses Pogossian reminded the audience that in the last eight years, the series has performed no less than 76 pieces by Mansurian. UCLA, moreover, will offer a Mansurian tribute on Jan. 26, which further fills in the gap.

Dilijan, instead, offered clues to how Mansurian came to create a style grounded on Armenian tradition yet internationally cosmopolitan, at once folk-based and revolutionary. Bartók, who did just that with Hungarian music, was an obvious model, and Mansurian's earliest piece of the afternoon, Allegro Barbaro for violin and piano, took its inspiration from Bartók's piano solo of that title.

At a time when accessible social realism was demanded of Soviet composers, Mansurian's brutish percussive Modernism was bold for a 25-year-old in 1964. Bolder still was Mansurian's 1966 Schoenbergian Second Violin Sonata, the first 12-tone Armenian piece.

How did Mansurian get away with it? The third weapon in his secret arsenal was sophisticated refinement. The boldness was in the technique, but the actual impression made by these pieces — to which Pogossian and pianist Mark Robson brought a commanding focus and intensity — is that of a fastidious attention to harmonic detail and a singing quality to Mansurian's melodies that no brutality can undercut (yet a fourth secret weapon).

Within the next few years Mansurian became increasingly avant-garde but also more nationalistic, incorporating traditional Armenian modes and melodies. He also became increasingly adept at covering his radical tracks by applying rigorous structure to override sentimentality.

Madrigal No. 1 — a setting of a tenderly morose Armenian text for soprano flute, cello and piano — and the chamber score "Tovem" were the works Sunday from the 1970s. In both, a vocal line or flute solo might have a sinuously melismatic Armenian flavor yet be constructed from rigorously mathematical principles.

Here, a listener might still be aware of two worlds in opposition. In the new pieces, those worlds became one. Armenian clarinetists commonly play the folk instrument, the duduk (or gralnet) on the side. In Mansurian's 2011 clarinet solo, "Parable," the composer narrows in on the common language between the two instruments.

For "Lotos," a 2012 viola solo, Mansurian's fascination was with the molecular structure of the lotus flower, which repels dust. Using an Armenian modal structure, he came up with yet another musical parable. The fleshy purity of Mansurian's viola writing is such that a writer has little hope of attaching an evocative description that will do it justice.

A few more hints at Mansurian's evolution were also offered Sunday, with works by two of his Armenian precursors. Three songs by Romanos Melikian from early last century were exotically tinged. The Lebanese Armenian Boghos Gelalian's "Sept Sequences," (written in the mid-1960s and possibly a world premiere) had a Middle Eastern Stravinsky/Varèse character and sounded like something Alfred Hitchcock might have wanted as a soundtrack for a mystery set in Beirut.

Dilijan made its own contribution to an afternoon of secret weaponry — uniformly terrific performances. The lineup included soprano Shoushik Barsoumian, clarinetist Phil O'Connor, violist Robert Brophy, cellist Antonio Lysy and conductor Vatsche Barsoumian.

Newsfeed

Videos