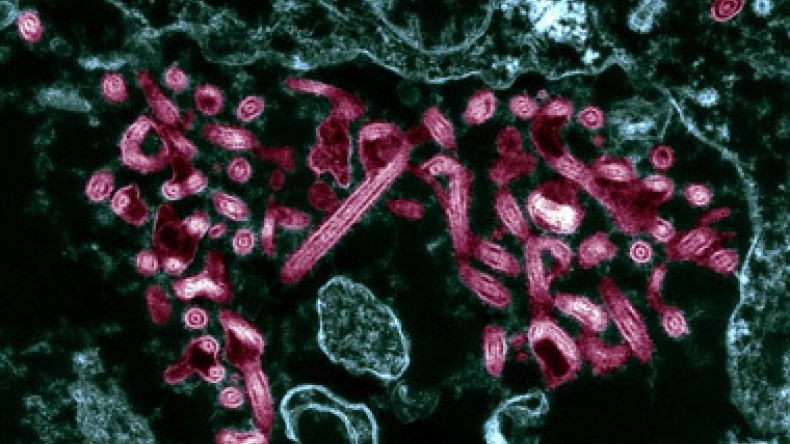

Ebola virus: Scientists discover DNA could determine if victims live or die

Genetics will determine whether a person infected with Ebola dies, scientists claimed, the Daily Mail reports.

A new study has found DNA could be the key to tracking the deadly effects of the virus which has ravaged West Africa.

The World Health Organisation revealed nearly 5,000 people have died from the disease, which has devastated Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

A team of scientists at Washington University believe their study has identified genetic factors behind the mild-to-deadly range of reactions to the virus.

Some people exposed to the virus completely resist the disease.

Others suffer moderate to severe illness and recover, while those most susceptible succumb to bleeding, organ failure and shock.

Past studies of people who have contracted Ebola found these differences are not related to any specific changes in the virus itself, making it more or less dangerous.

Instead the body's attempts to fight infection seems to determine the severity of the disease.

Researchers believe their new findings could accelerate vital drug and vaccine development, reflecting the diversity of reactions to the virus.

The study examined how the disease affects mice.

Study leaders Angela Rasmussen and Michael Katze said research on Ebola has to date been hampered by the lack of a mouse model that replicates the main characteristics of human Ebola.

Their study was conducted in a highly secure, state-of-the-art biocontainment lab in Montana.

The scientists examined mice that they infected with a mouse form of the same species of the Ebola virus responsible for the current West African outbreak.

Conventional lab mice previously infected with the strain of virus died, but did not develop symptoms of the disease.

In the new study, researchers noted all the mice lost weight in the first few days after infection.

However, nearly one in five (19 per cent) not only survived, but also fully regained their lost weight within two weeks.

They showed no signs of having any gross pathological evidence of disease and their livers appeared normal.

One in nine of the mice (11 per cent) were found to be partially resistant and less than half of them died.

Seventy per cent of the mice had a greater than 50 per cent mortality, with 19 per cent of this last group suffering liver inflammation despite not showing the classic symptoms of the virus.

A third had blood that took too long to clot - a hallmark of fatal Ebola in humans.

Those mice also suffered internal bleeding, swollen spleens and changes in liver colour and texture.

Dr Rasmussen said: 'The frequency of different manifestations of the disease across the lines of these mice screened so far are similar in variety and proportion to the spectrum of clinical disease observed in the 2014 West African outbreak.'

While acknowledging that recent Ebola survivors may have had immunity to this or a related virus that saved them during this epidemic, Dr Katze said: 'Our data suggest that genetic factors play a significant role in disease outcome.'

Newsfeed

Videos