Human leg bones have grown weaker since farming was invented

Farming may have brought with it a host of benefits on diet and the economy, but it also caused us to become weak and puny, the Daily Mail reports.

Research, covering a period of more than 7,000 years of human evolution, has revealed modern-day skeletons are lighter and more fragile than those belonging to our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

In fact, the bones of our early ancestors were comparable in strength to modern orangutans, but once farming spread, these bones became 20 per cent weaker.

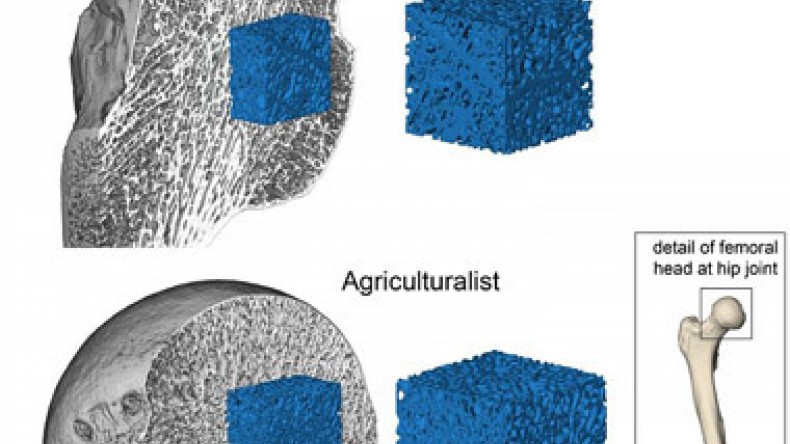

Researchers from the University of Cambridge used X-rays and CT scans to study ancient samples of human femur bones, along with femora from other primate species.

In particular, they focused on the inside of the femoral head - the ball at the top of the femur which fits into the pelvis to form the hip joint.

This joint is one of the most load-bearing bone connections in the body.

There are two types of tissue that form bone. The cortical or 'hard' bone shell on the outside, and the trabecular or 'spongy' bone on the inside.

This trabecular bone is a honeycomb-like mesh inside the cortical shell that allows flexibility, but is also vulnerable to fracture.

The bones studied covered four distinct archaeological human populations representing mobile hunter-gatherers from 7,300 years ago, and more recent, sedentary agriculturalists.

All were found in the same area of Illinois, and were therefore likely to be genetically similar.

The trabecular structure was found to be very similar in all populations, but the hunter-gatherers had a much higher amount of actual bone relative to air.

'Trabecular bone has much greater plasticity than other bone, changing shape and direction depending on the loads imposed on it; it can change structure from being pin or rod-like to much thicker, almost plate-like. In the hunter-gatherer bones, everything was thickened,' said lead researcher Dr Colin Shaw.

This thickening is the result of constant loading on the bone from physical activity as hunter-gatherers roamed the landscape, seeking food.

This exertion would result in minor damage that caused the bone mesh to grow back stronger and thicker throughout life - building to a 'peak point' of bone strength, which counter-balanced the deterioration of bones with age.

Bone mass was around 20 per cent higher in the foragers - the equivalent to what an average person would lose after three months of weightlessness in space.

And after ruling out diet differences and changes in body size as possible causes, researchers concluded a drop in physical activity are the root cause of degradation in human bone strength across millennia.

They believe the findings support the idea that exercise, rather than diet, is the key to preventing heightened fracture risk and conditions, such as osteoporosis, in later life.

The research also counters the theory that, at some point in human evolution, our bones just became lighter - perhaps because there wasn't enough food to support a denser skeleton.

'If that was true, human skeletons would be entirely distinct from other living primates. We've shown that hunter-gatherers fall right in line with primates of a similar body size.

'Modern human skeletons are not systemically fragile; we are not constrained by our anatomy,' said Dr Shaw from the university's Phenotypic Adaptability, Variation and Evolution (PAVE) Research Group.

'The fact is, we're human, we can be as strong as an orangutan - we're just not, because we are not challenging our bones with enough loading, predisposing us to have weaker bones so that, as we age, situations arise where bones are breaking when, previously, they would not have.'

Newsfeed

Videos