Las Vegas Armenians remember tragic history and genocide

Below we present an article by Michael Lyle published in Las Vegas Review-Journal.

In 1915, an estimated 1.5 million Armenians were systematically exterminated, about 30 years before there was even a word for what that was — genocide.

Although it is rarely talked about in history classes or among the general public, the Armenian-American community vows to never stop raising awareness of this tragedy.

“Just because people in the U.S. don’t know about it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be telling our story,” says Andy Armenian, a member of the Armenian American Cultural Society of Las Vegas. “It’s important for our community as well as the general public to know this story.”

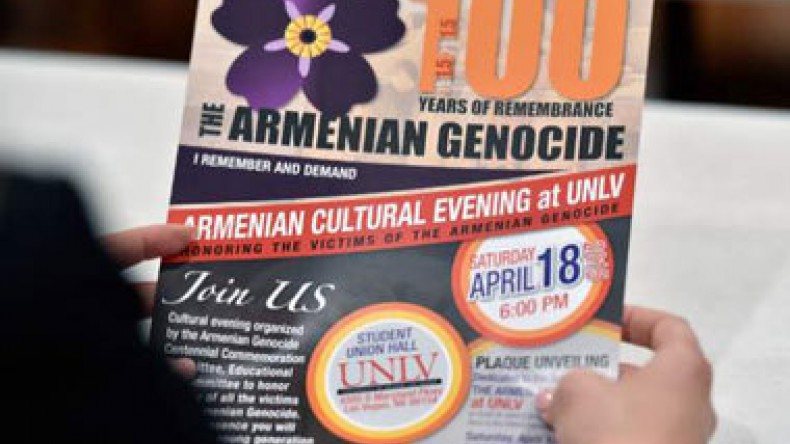

This year is the 100th anniversary of the start of the genocide, which the organization plans to commemorate on April 24 by hosting a groundbreaking for a memorial at Sunset Park, 2601 E. Sunset Road.

Gov. Brian Sandoval has also issued a proclamation declaring April 19-26 “Days of Remembrance of the Armenian Genocide.”

Whether it’s through the memorial or just talking about their heritage, the Armenian community thinks it’s time for people to know about their history.

Michelle Tusan, a history professor at UNLV and author of “Smyrna’s Ashes: Humanitarianism, Genocide and the Birth of the Middle East,” says Armenians had a long history of being discriminated against prior to 1915.

Under the cover of World War I, the Ottoman Empire — the historical name for Turkey — began to act on its hatred for Armenians, who were among the Christian minorities in the country.

“There was a lot of resentment toward that community,” Tusan says. “They were also paranoid that (Armenians) were siding with the enemies.”

On April 19, 1915, Armenian civilians began being rounded up. Five days later, on April 24, 250 intellectuals and Armenian leaders were killed.

“And that was the beginning,” Tusan says.

The government separated the men from women and children, killing many men of military age.

During the next year, women and children were moved to relocation camps.

“You didn’t have gas chambers,” Tusan says. “But you did have concentration camps. But it started with what was essentially known as a death march.”

Those who were forced to make the journey to the camps were sent along the way with little to no supplies.

“Then they would arrive to these camps and have very little there,” she says.

Andy Armenian says about 70 percent of Armenians were killed.

“The other 30 percent escaped either going east or south to other Arab countries,” he adds.

At that time, many of those families sought asylum in the United States.

Much of the history during that time is lost. What few photographs there are were taken either by German soldiers or missionaries in the region.

Turkey still doesn’t recognize the actions as genocide.

Armenian says under international law, if Turkey acknowledged the genocide, it would have to pay reparations and possibly sort out which land was stolen from the Armenians.

“I think it also goes deeper into the Turkish identity,” Tusan says. “For them to acknowledge this would mean rethinking their whole history. Look how much Germany’s history was shaped postwar.”

The United States has failed to pass a resolution that acknowledges the genocide even though many politicians agree it is something that happened.

“It’s a hot-button issue, because Turkey is an ally,” Tusan says.

She adds that when the topic is brought up for Congress to pass a resolution acknowledging the history, Turkey makes threats about its alliance with the U.S., which also means putting the United States’ standing in the Middle East in jeopardy.

“It goes back to geopolitics,” she says.

Even though the United States hasn’t voted on a resolution, many states, including Nevada, have adopted state resolutions.

No matter what the rest of the international community says, Armenians never forget the stories that are passed down through the generations.

Armenian says even 100 years after the genocide, Armenians still feel remnants of the tragedy.

“Genocide has affected every single one of us,” he says.

One of the byproducts is constantly being uprooted, Armenian adds.

“Whenever there is turmoil in the Middle East, we see a new wave of immigrants,” he explains.

For example, in the mid-’70s during the Lebanese civil war, more than 100,000 Armenians — his family included — fled to the United States.

Another huge number of Armenians left Iraq between 1987 and 1990.

“The Armenian population in Iraq is almost nonexistent now,” he says.

While some families journeyed to the United States later, Armen Anooshian’s grandmother came to New York after fleeing Turkey in 1915.

“Most survivors ended up either on the East Coast or the West Coast,” Anooshian says. “Because all their family members had died in the genocide, the community was one big family.”

Anooshian says it’s nearly impossible to grow up in an Armenian community without hearing someone bring up the history in conversation.

In New York City, where he was born and raised in an Armenian neighborhood, his grandmother along with other women would talk about how she survived.

“You would always overhear stories when you were a kid,” he says.

Jack Kassamanian, born and raised in Chicago, never met his grandmother, who also survived the Armenian genocide. He does remember seeing her photos, in which she had a scar on her cheek.

“I was told she was shot in the cheek while she was trying to flee,” he says.

The stories aren’t isolated to families. Kassamanian says Armenians usually gravitate toward each other to develop a community.

With that in mind, the Armenian American Culture Society of Las Vegas was founded in 1978 but wasn’t established as a nonprofit until 1981.

“Its purpose is to preserve the Armenian tradition, history, language and culture,” Armenian says.

A central point for gatherings has always been a church, Anooshian notes. St. Garabed Armenian Apostolic Church was established in 1994 but opened a permanent location at 2054 E. Desert Inn Road two years ago to provide a place for the community.

Armenian says two more churches are being constructed in the valley.

In the courtyard of St. Garabed Armenian Apostolic Church is a statue known as “The Surviving Mother,” which is in honor of all the mothers who survived the genocide.

For the past few years, the organization has discussed a permanent memorial in Las Vegas that would recognize Armenian genocide.

Anooshian says other cities in the U.S. — San Francisco, Los Angeles, Philadelphia — have versions of a memorial.

“The largest one is in Montebello, (Calif.),” Kassamanian notes.

The group wanted the memorial placed in Sunset Park because of the park’s central location in the valley. The groundbreaking for the memorial April 24 will also include a candlelight vigil.

Kassamanian says the memorial is being designed by Levon Gulbenkian, board president of the Armenian American Cultural Society.

After looking at models across the country, Kassamanian says the design includes 12 pillars that represent a lost province during the genocide while the bench in the center of the pillars has the Armenian symbol for eternity.

He adds they hope to have the memorial finished in September.

“It will coincide with the Armenian independence,” he says.

The memorial costs $200,000 and is funded through private donations.

“We are a little over 50 percent done with fundraising,” Kassamanian says. “We could always use more donors. We estimate we should have all the money by the time the memorial is finished.”

Although April 24 is the day of remembrance for all Armenians, the organization has events planned throughout the month.

Besides the larger memorial at Sunset Park, the Armenian American Cultural Society is getting a memorial plaque at UNLV.

On April 18, Armenian says an Honorary Consul of the Republic of Armenia is opening in Las Vegas.

Besides preserving Armenian culture, the consulate will provide resources to new and current citizens and work to help economic development between Nevada and Armenia.

Each accomplishment helps to bring a little more recognition to this issue, Armenian says.

“We have to learn from this tragedy so we don’t repeat it,” he adds.

Newsfeed

Videos