26 years after genocide of Armenians in Azerbaijan: “I remember Baku and again feel smell of burnt human flesh…”

Panorama.am has already reported that a collection book Baku Tragedy: Eyewitness Accounts is to be published in the frameworks of the project Ordinary Genocide. It is going to include the interviews of about 50 refugees currently living in the US who speak about their memories. ‘A Century-Long Genocide. Black January of Bakuhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COmtRTW0A9w, a film, whose presentation took place a year ago, was made based on those accounts.

To commemorate the 26th anniversary of the genocide of the Armenians in Baku, Panorama.am goes on publishing chapters from the future book, provided to the website by Marina Grigoryan, the manager of the project an Ordinary Genocide.

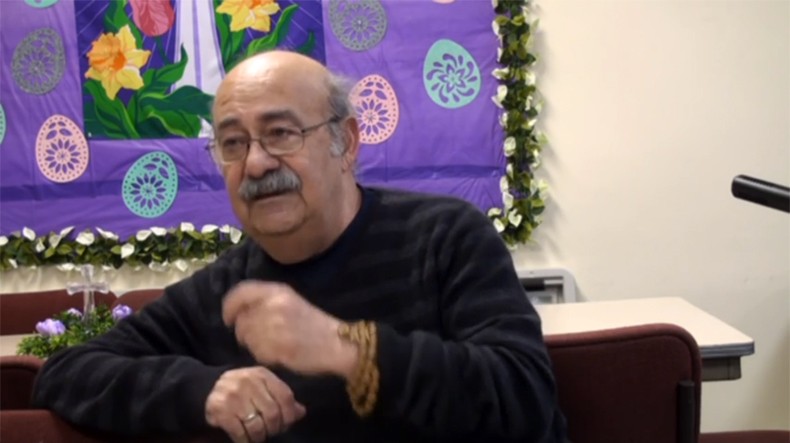

Valery Mikhaylovich OHANOV

I was born in Baku in 1942. I grew up and lived in that city. My great-grandparents, my father are buried there. I can remember very well my last day there. It was in January 1990. God must have saved me back then.

My mother lived in Montino, and I lived in a microdistrict with my family. After Sumgait, outwardly little changed in Baku, only people started to fear. It was very scary to live, really scary. Something could happen any day. What saved me was that I spoke a good Azerbaijani, and besides, my face is not prominently Armenian. The Armenians were told at work that they needed to leave, that it was dangerous to stay. Demonstrations were held in the city, and it was impossible to appear in those places or just pass by. By that time, my son was being enrolled at an institute, the AII (Azerbaijan Industrial Institute, now Azerbaijan State University of Oil and Industry, – ed.). He was already a grown-up boy, but I went to all the exams with him to protect him in case anything happened. But what could I do against a mob? After all, we heard, we knew what was going on in Sumgait.

I took my wife and children to Yerevan in December 1988. It was already impossible to stay in Baku; my son couldn’t go to the institute, neither my daughter to school. I had to be on the alert all the time. Some cases already happened in our microdistrict; the windows of an Armenian flat had been broken. I had such a work that I needed to move mainly in car. But even with this, I witnessed attacks on Armenians. Once I went to the AII and saw how a mob was beating someone, I couldn’t even see who it was.

I sent my family to Armenia on December 1, and the earthquake occurred on the 7th. My cousin lived in Spitak, her son was killed there during the earthquake. His name was Valery in my honour, the boy was only 10. I can remember very well how people in Baku were glad for that, how they celebrated, danced… I saw it myself, I heard someone shout the word ‘Spitak’ – ‘spi tak.’ Of course, there we people who sympathised with us, still they were very few.

My mother stayed in Baku up to the end trying to sell her flat in Montino and buy some living in Yerevan so that we could accommodate ourselves somehow. My wife and daughter were in Krasnovodsk by then, and I was in Yerevan with my son; it was already a year he had been studying there. And I had to go back to bring mom. There were no planes flying from Yerevan to Baku or backwards anymore. I remember arriving at the airport Erebuni and seeing a crowd standing as they wanted to depart. It was on January 13th, by the Old New Year. I departed to Tbilisi, and to Baku from there. When I got off the Tbilisi flight in Baku airport, I accidentally met a friend, an Azerbaijani I used work with. Seeing me, he asked me frightened, “Where are you going?” I explained him that I had arrived to take mom. He said, “I wouldn’t advice you go into the city. Immediately go back.” But I couldn’t leave my mother. I took a taxi and went to her. I knew that my flat was occupied for a long time already, as we hadn’t sold it; we left everything and departed.

The city was in unrest, there were many people in the streets, shouts, demonstrations. The windows of her flat were dark, while there was a light in the neighbouring ones. I turned around; there were a lot of people around. I started to make inquiries in Azerbaijani and understood that either she wasn’t there or something had happened. I went to my friend who lived in the neighbouring microdistrict, and started to call neighbours, friends. And I found my mother. I was told not to worry; they said they would take her to me. An acquaintance of ours ran up on the 14th late in the evening and said, “Uncle Valera, leave, they said you are at this person’s home (I don’t want to mention his name, he is half-Azerbaijani and half-Armenian).” I didn’t want to let him down. I called and asked to take my mother to Shafag; it is a cinema on Lenin Avenue. The Armenians were being gathered there. And I went out. I took a taxi and went to the bloc where I had grown up. I walked and felt smell of burning, of burnt flesh…

In order to go up to Shafag, I had to go through a crowd of 50 people at width and reach the soldiers with shields. I reached them. I told s soldier to let me in. He demanded a passport. I told him if I showed my passport, I wouldn’t get in anymore. And then an officer told him to let me in. I went into the cinema and waited. A friend brought my mother. She had a small bag with her and could hardly walk. She saw me and fainted. It is very difficult to remember this all…

I had money with me, as I knew where I was going. I tried to help the people in Shafag, many were brought literally undressed, and it was rather cold. I remember an old woman, she was married with an Azerbaijani and had three sons. She said when they came to take her out, her sons started to shout, they wanted to keep her at home, but nothing helped. The Popular Front had already joint them by then, and wanted to show that the Armenians were being taken out of Baku peacefully. We were told we would be taken to a ferry. I can remember a girl shouting all the time, “Uncle, we’ll be killed.” And I calmed her down.

We were taken to the port on buses. I had often gone to Krasnovodsk (my wife’s sister lived there) on a ferry, that’s why I knew many of the captains. There were about thousand or a little more of us on the ferry. Everyone was driven to the holds, the cabins were closed. I went up to the captain, gave him money and asked him to open the cabins and accommodate old and sick people there. There were almost no young people there, children were few, as well. But there were really many old people. Those were elderly, sick people who hadn’t been able to leave and hadn’t even thought of that. They were in a very bad state – beaten, undressed, shocked, in an awful stress…

The youngsters of the Popular Front searched for us on our way to the ferry. The people were placed in the decks and in the cargo compartments, the holds. The Popular-Fronters didn’t allow to place the sick, old, beaten people in the cabins, and they were, I’m repeating, the 99 percent of the passengers. While the cabins were not cold at least. We left at the night between the 14th and 15th. There was talk that there were many killed on the first two ferries that had set out into the sea before us. I don’t consider myself a coward, but even now, I sometimes wake up of fear at nights, of fear of persecution.

I’d like to highlight that we were very warmly met in Turkmenistan. My daughter and wife met me in Krasnovodsk. I remember how my daughter threw herself on me, hugged and started to cry, to sob… The last time I had called them from Baku, from a friend’s home, I told my wife, “Take care of the children, see that everything is alright.” She asked me when I would go to them, and I answered, “You take care of the children.” And she understood that everything was bad, dangerous.

To be honest, I loved Baku very much. It is the city where I grew up, where I know every piece of stone. Meanwhile, I often went to Yerevan, I had many relatives there. Who could only think that this would happen… We, the Baku residents, still look for each other. We call each other and say that someone appeared somewhere, or that the other is here. There were two more with me on the ferry, and we helped each other. One of them again went to Baku later, his wife told me. I still don’t know what happened to him. He didn’t come to the meeting the three of us had planned.

I still see all that in my dreams very often, although so many years have passed. I think I could get out alive from there only by God’s will. I see in my dream the place that I went very seldom, when I had trouble. And that smell… the smell of the burnt human body… That smell doesn’t leave me. I’m talking to you now and I feel it.

Hartford, Connecticut, US. 25.03.2014.

A mass pogrom of Armenian population was committed in Baku from 13 to 19 January 1990 as a culmination of the genocide of the Armenians in Azerbaijan unfolded between 1988 and 1990. After the Sumgait pogroms (26-29 February 1988), persecutions, beatings, particularly cruel killings, public mockeries, pogroms of separate flats, seizure of property, forcible expulsions and illegal dismissals of Armenians started in Baku. Only some 35 or 40 thousand Armenians of the community of 250 thousand remained in Baku by January 1990; they were mainly disabled people, old and sick people and the relatives looking after them. The pogroms took an organised, targeted and mass nature since 13 January 1990. A large amount of evidence exists about the atrocities and killings committed with exceptional cruelty, including gang rapes, burnings of people alive, throwing people out of balconies of higher floors, dismemberments and beheadings.

The exact number of the victims of the genocide of the Armenians in Baku still remains unknown. According to different sources, between 150 and 400 people were murdered, and hundreds were left disabled. The pogroms went on for a week amid a total inaction of the authorities of Azerbaijan and the USSR, as well as the internal troops and the large Baku garrison of the Soviet Army. Those who managed to avoid death were forced into deportation. The Soviet troops were deployed to set order in Baku only on 20 January 1990.

For more detail, visit KarabakhRecords

Related news

- “This is impossible to forget and to forgive”: A Century-Long Genocide. Black January of Baku film demonstrations in US

- 26 years after genocide in Baku: “They called and threatened to finish off with us as they had done with our niece in Sumgait”

- 26 years after genocide in Baku: “Baku received order from Moscow not to intervene in pogroms and allow them easily slaughter Armenians”

- 26 years after genocide in Baku: “They marked Armenian flats with crosses to come and attack later”

- 26 years after genocide in Baku: “My mom listened to Sayat-Nova and cried – her father survived Genocide, then she herself became refugee”

- 26 years after genocide in Baku: “They just threw that young Armenian under train”

- 26 years after genocide in Baku: “Someone informed pogromers that young Armenian woman hid in that house, and they came after me…”

- ‘History repeats itself…’ ‘A Century-Long Genocide. Black January of Baku’ film screened in Richmond

Newsfeed

Videos