Study: Hobbit not to be Homo sapiens but something much more exotic

In 2003, a mysterious tiny species of hominin (early human) was discovered on the Indonesian island of Flores. It was given the scientific name Homo floresiensis, but it is better known by its catchy nickname: "the hobbit," Melissa Hogenboom writes for the BBC.

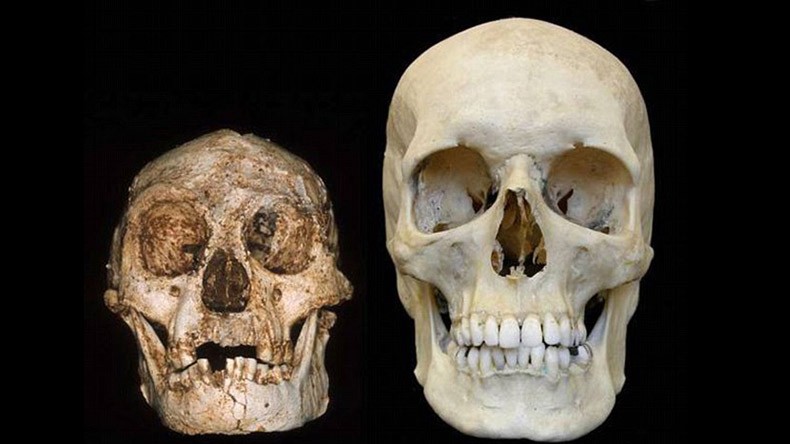

According to the author, nothing quite like the hobbit had been observed before in two million years of human evolution. For one, fully grown it was only about 3.5ft (1.1m) tall and would have weighed about 25kg. And, even more unusually, its skull was tiny: the hobbit’s brain would have been no larger than a modern chimpanzee’s.

The hobbit may have lived on Flores for about 100,000 years. About 15-18,000 years ago it disappeared forever.

This makes it the most recent other human species that walked the Earth at the same time as us, Melissa Hogenboom writes and adds that whether this creature represents a unique species or not remains an area of debate among paleoanthropologists. Some say it was simply a modern human with a form of dwarfism. Others have even proposed that the hobbit’s size – and in particular that tiny skull – was the result of a genetic disorder such as microcephaly or Down's syndrome.

Cut off from the rest of the world on Flores, this isolated habitat is another factor that could have caused it to evolve to such a small size. The island was also home to a dwarf elephant ancestor, for example. These ideas are heavily debated and a myriad of methods have been used to analyse the shape and size of the hobbit remains, the author notes.

The problem, says Antoine Balzeau of France’s Natural History Museum, is that many of these assertions focus on aspects of the skull that represent normal variation among hominins.

"You cannot argue that one feature is the definitive clue of the [species] if it's normal for many other fossils," Balzeau told BBC Earth.

A further issue, he says, is that many researchers who have studied the hobbit relied on casts or low resolution scans, which do not preserve important anatomical details. Balzeau considers the Flores remains to be the most important fossils discovered in recent years, so he wanted to get to the bottom of some of controversies around their identity.

Together with Philippe Charlier of Paris Descartes University, France, he looked at high-resolution images of the only complete cranium of the group – skull Liang Bua 1 (LB1) – to identify all the various points of thickness and composition of the bone. Even small changes or variation can give clues to which human species the hobbit most closely resembles. The resolution of the scans they used was about 25 times higher than that used in previous research.

They also looked at the interior parts of the skull to see how the various bone plates of the skull interlocked. "None of these features could explain the strange shape of the specimen," Balzeau says. "The shape of its skull is definitely not the shape of a modern human skull... Even a human with pathologies [disease]."

Taken together, the results of his study, soon to be published in the Journal of Human Evolution, suggest that there is nothing about the skull that fits with any known population of modern human. In other words, the hobbit is not a small and diseased member of our species, Homo sapiens. It is something much more exotic.

Crucially, the hobbit also lacked a chin. The very presence of a chin is a defining trait of our species. No other hominins possessed one. If anything, the hobbit was most similar to Homo erectus (another species of ancient human which is thought ancestral to us) than any other hominin, says Balzeau. This fits with the idea that the hobbit evolved from a population of this ancient human species.

That being said, the specimen remains strange. "Its eyes are very small and its shape is slightly different from H. erectus," Balzeau considers.

Some even argue that H. floresiensis is far too primitive to be attributed to our own genus, Homo at all. Some features of its skeleton seem to be more like those seen in a more "primitive" group of human-like apes called the australopiths. This would make the hobbit a close relative of the famous Lucy fossil, the most well known of all australopiths, the article reads.

"Many people who think it’s a modern human are medical doctors, so they make a diagnostic based on shared features that fit a certain disease or pathology," Balzeau says.

If we found a modern human that showed the exact same features of the hobbit, then that comparison might be valid. But, as far as we know, no such human exists.

However, Robert Eckhardt of Penn State University, US, maintains that the LBI individual was a modern human with a genetic condition. "The new study does not show that LB1 has a cranial bone thickness that requires its designation as a separate species," he says as cited by the BBC. There is no evidence that the remaining 11 or 12 individuals appear abnormal.

Further, as there is only one complete hobbit skull, we do not know what the heads of others would have looked like. This makes the designation of a species from only one cranium problematic, adds Eckhardt.

Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum of London in the UK, told the BBC dating studies might provide new insights, but for now we cannot definitely confirm the hobbit’s species status.

Newsfeed

Videos