Aris Ghazinyan: In beginning of 19th century Armenian population had to survive and preserve “Armenian Yerevan”

Countless times the trace of the “Yerevan demography” challenged the hard Armenian perspective and called it to the barrier, countless times it tried to establish an “Armenian exile.” But every time Yerevan could rise from the ashes, every time it could find power for the reproduction of its native elements. Armenian journalist and researcher Aris Ghazinyan writes about it in his book “Yerevan: with a cross or on the cross,” which is an attempt of setting and considering an extremely diverse range of processes directly or indirectly forming the character of the development of the territory in question and predetermining the inevitability of turning Yerevan into the main center of the Eastern Armenia, and later on into the capital of the recovered Armenian state.

Ghazinyan writes about the structure of the Yerevan population in the beginning of the 19th century, and about how it was distributed. The Armenian population of Yerevan was concentrated mainly in Shahar, Tapabash, and Dzoragyugh. Shahar or Shehar (meaning "town" in Persian) was situated in the central part of Yerevan.

To the north of Shahar, on the Kond height and rising feet, Tapabash region was situated. In the beginning of the 19th century, six hundred Armenian families (about three thousand people) lived there.

To the west of the Kond hill, Dzoragyugh was located. It was a peculiar Armenian region on the left side of Hrazdan ravine. The development of this district was of a terrace type, in the form of parallel tiers laid along the riverbed.

The Armenian population also lived in the northwestern hills (Nork-Cholmakchi, Kanaker, Avan), western (Norachen, Kavakert), and southern (Noragavit) regions, which had been long situated within the boundaries of the Armenian capital. After the catastrophic Garni earthquake, churches were built in these regions: St. Astvatsatsin (in Nork), St. Hakob and St. Astvatsatsin (in Kanaker), St. Gevorg church (in Noragavit), several chapels in Avan, and necropolis in Arinj.

This was Yerevan’s approximate description in the beginning of the 19th century. The number of the residents was about 12,000 with the Armenian population dominating over the others. Taking into account that Arabian, Persian, and Turkic were the official languages in the territory of the historical Armenia for a thousand years, and all the important documents and logs of taxable population were made up in these languages, a large amount of Muslim terms connected with various aspects of life appeared in the lexicon of the Ararat dialect of the Armenian language.

These are the toponyms, to which Turkish and Azerbaijani authors like to refer (Basarkechar, Kyamarlu, Amamlu, Sardarabad, Jalaloglu, Uchkilise, Zangibasar, Gharaqilisa, Gyumri, etc.) and purely domestic – “changal” ("knife," Armenian “patarakagh”), “khiyar” ("cucumber" - "varung"), “kyalam” ("cabbage" - "kaghamb"), “nardvan”, “pilaqyan” ("step ladder," "ladder" -"astichan," "sandughq").

However, at the beginning of the 19th century, the problem the Armenian population faced was other than a purely lexicological one. It had to survive somehow and preserve the “Armenian Yerevan,” a fact Abovyan himself recognized: “There were hard times, people only thought about how to remain intact and keep their head on their shoulders. How could one care for the language!”

Hope sparked in the hearts of Yerevan people in November 1808 as the commander of the Russian troops in Georgia and Dagestan, general Ivan Gudovich, replacing Pavel Tsitsianov, started an assault on the Yerevan fortress.

However, as the war dragged on, and there was no opportunity of continuing it further in the new political conditions, soon he had to renounce his plan of capturing the impregnable fortification.

At that time, Russia was waging a parallel war with the Ottoman Empire, there were also military operations in Ossetia, and Russia was about to be invaded by Napoleon’s army. That is why the Russian commanders decided to give up the ambitious plan till things went better. Moreover, the-nine year war turned out to be a successful one: in 1813, in the Karabakh settlement Gulistan, a treaty was signed, according to which Persia agreed to cede almost all the Georgian lands, as well as most of the Transcaucasian khanates (Baku, Quba, Karabakh, Shaki, Ganja, and a part of Talysh) to the Russian Empire.

“As for the Yerevan khanate, Russia recognized it ‘under the absolute power of Persia.’ The war was really successful for Russia, but not for Yerevan, as the signing of the Treaty of Gulistan was a blow to the Armenian population of the city. After the 1804 and 1808 unsuccessful attacks on the fortress and the shift of the gravity center of the military action to the Eastern Transcaucasia, the population clearly realized the impossibility of the city’s transition under the Russian jurisdiction. But will another campaign take place?” Ghazinyan writes noting that this very question oppressed the Yerevan people most of all.

The first article of the treaty unambiguously stated: “Hostility and disagreements existing hitherto between the Russian Empire and the Persian State are ending with this treaty, and let there be peace, friendship, and kind consent between H.I.M. Own Chanceries Russian Czar and Persian Shah, their heirs and descendants of the thrones, and their great empires.”

After “mutual state ratifications exchanged by mutual plenipotentiaries," it became clear that in the visible future, Yerevan could become a Muslim city. The Treaty of Gulistan was advantageous for the Russian Empire, which finally captured Transcaucasia and, therefore, got the opportunity of focusing its main attention on Europe.

“In addition to this, the mass outflow of the Christian population out of the Yerevan Khanate’s borders, and, which is especially important, the successful adoption of new lands by Yerevan people, created favorable conditions for their final abandonment of the native town. They got the opportunity of possessing not only the Caucasian territories, but also the original Armenian ones – Syunik in the south, Artsakh in the east, Lori in the north, which were included in the Russian territory according to the Treaty of Gulistan,” Ghazinyan writes noting that only destruction, humiliation, and intolerable life conditions awaited the Armenians in Yerevan.

The Persian rulers sincerely wanted to believe that soon no Christian would be left in the governorate, and Russia would lose its interest in that “alien, purely Muslim land,” the author emphasizes.

The Treaty of Gulistan created objective prerequisites for Yerevan's quick transformation into a purely Muslim colony. The Qajars were in a great euphoria.

However, the court of the shah was clearly aware of Yerevan's "explosibility," and the shah realized that even after the signing the “eternal peace” with Russia, none of the sides was insured from a new war. “Therefore, the consolidation of the Turkic element in the city, the strengthening of its position, and the provision of the Muslims’ quantitative preponderance was – in the aspect of the Qajars’ interests – a strategic issue, especially against the pro-Russian orientation of the Armenians and the active role they had played during the last campaign,” Ghazinyan writes.

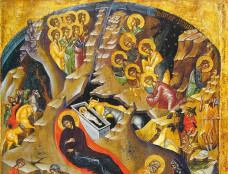

The strong belief in the invulnerability of their positions defined the forms and scales of mockery and violations towards the Armenians. The Armenian clergy was made to accompany the sardar and his brother Hasan-khan “according to strict rites” during walks along the city: with cross and gonfalons, bell-ringing and singing sharakans – Armenian spiritual hymns. Priests from Dzoragyugh, Kond, and Shahar had to meet them, whereas the Muslims were ordered to "mock at the clergymen.”

In the years of Huseyn Kuli-khan’s ruling, melik Sahak was the leader of the Armenians in Yerevan. Although the prince was among the Persian garrison and was the commander of a special Armenian detachment, he was popular with the people.

To be continued.

Aris Ghazinyan’s “Yerevan: with a cross or on the cross” is a book about the social and political history of Yerevan and Yerevan district (as a habitat) since the declaration of Christianity to the beginning of XIX century. In addition to demonstrating historical facts based on archive documents and sources, the book also considers the fundamental theses of the Azerbaijani historiography and Pan-Turkic ideology aimed at appropriating the historical, cultural, and spiritual heritage of the Armenians and other nations of the region by falsifying their history.

Related news

Newsfeed

Videos