UNICEF: More than 1 million children in Afghanistan at risk of starvation

UN News spoke with Samantha Mort, Chief of Communication, Advocacy and Civic Engagement at UNICEF Afghanistan, who assured that all offices remain open and warehouses full.

Some 22.8 million people across the country are facing food insecurity, she explained, adding that they cannot access affordable or nutritious food.

Of the 38 million people living in Afghanistan, some 14 million children are food insecure.

For Ms. Mort, “there's no childhood” these days in Afghanistan. “It's all about survival and getting through the next day.”

‘The perfect storm’

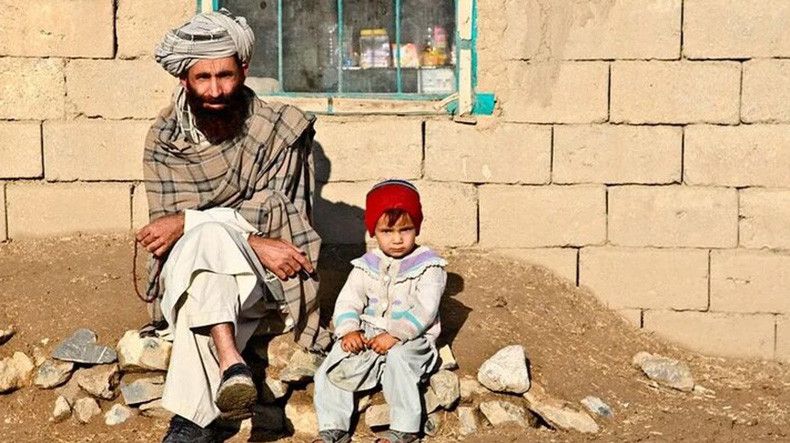

She painted a grim picture of impoverished families in which parents are not eating three meals a day, meal portions are decreasing and people wake up not knowing where the next meal is coming from.

“It's that level of food insecurity”, said the UNICEF official.

Exacerbated by drought, a poor harvest and rising food prices, she referred to the looming crisis as “the perfect storm in Afghanistan”.

And at the start of a typically freezing cold winter, Ms. Mort said that snow would cut off rural areas in the mountains.

“UNICEF is very, very concerned because what we are seeing is around 3.2 million children who are acutely malnourished and 1.1 million children who are at risk of dying because of severe, acute malnutrition unless we intervene with treatment”, she warned.

Hospital records

Last week, the UNICEF official visited health clinics in the western part of the country.

At the one, the doctor shared records showing a 50 per cent increase in cases of severe malnutrition while another revealed a 30 per cent rise.

Despite the increase, Ms. Mort explained that the crisis did not start on 15 August but that the country had been experiencing some form of insecurity or conflict for the last 40 years.

“But because of the drought...poor harvest...rising food prices, because many women have been asked to stay at home since August 15, a lot of families have lost their main source of income”, she said.

A family story

Ms. Mort recalled that she had asked the mother of a severely malnourished baby if she was breastfeeding and was told that despite trying, she had no milk. A doctor in the room asked the woman if she was eating. The woman replied that most days, she only drank a glass of black tea with a piece of bread in it.

“It's no wonder that she can't breastfeed because she is undernourished herself. And I think that is a story that is amplified all over the country”, the UNICEF official said.

Another mother brought in her 4-year-old, wearing an oversized coat.

“You'd expect the 4-year-old to be looking around and be curious about the strangers in the room. This little girl sat supported by her jacket in the same position as her mother had put her down. And she just stared at the floor. Her head was bowed. She had no energy”, Ms. Mort recalled.

Removing the young girl’s coat, her little arm was “no thicker than a broom handle” and she was so malnourished that her hair was falling out and her cheeks were hollow. At 4 years old, she weighed about 20 pounds.

“Severe, acute malnutrition means that you can potentially die if you are not treated. And that means that if we do not treat them, they will die”, Ms. Mort said.

Doubling efforts

Because of the drought and resulting poor harvest, UNICEF is predicting that food stocks will run out halfway through winter.

The agency is doubling its number of nutrition counselors and mobile health and nutrition teams that can go into rural communities to help the children hardest to reach.

Ms. Mort highlighted that the nutrition counselors are often recruited locally so that communities trust them.

“They're very passionate...energetic and...uplifting”, she explained pointing to positive interactions between them and the mothers who come for help.

“They come up with creative solutions. They use what is in the community. They share resources”, she explained.

These professionals are typically also young, educated women. Ms. Mort remembered meeting a female doctor in her early 30s who was running a medical clinic with 20 staff, 18 of whom were women.

The doctor found it “tremendously uplifting to see young professional women working in Afghanistan...amidst all the challenges”, recalling that they “wouldn't stop talking about their their work, about their patients”.

Uncertain future

Throughout her visits, Ms. Mort mostly observed feelings of uncertainty.

“I think people are uncertain, they don't know what the winter holds, what the de facto authorities are going to do next. They don't know if the international community will deliver on these funds so that the health system and the education system recover. It feels as if everybody is in a bit of a holding pattern”, she said.

For the UNICEF official, it is “absolutely critical” that the international community understands that Afghanistan is on the brink of a humanitarian crisis.

“This is not time for political brinksmanship. People in Afghanistan are dying, and they need our support. Humanitarian aid is the last expression of human solidarity”, she said.

“When you have nothing...are struggling...feel forgotten...[and] don't know where your next meal is coming from, humanitarian aid arrives at your door and you are part of a much larger family”.

Health sector in crisis

Ms. Mort recalled a conversation she had last week with the director of the Indira Gandhi Children's Hospital in Kabul who told her that sometimes he has three babies in a single bed, because so many of the district and regional clinics can no longer operate.

Moreover, people living rural areas have to take their babies to the capital. But because poverty restricts their ability to travel, they wait so long that their children have gotten very sick.

“Often, it’s too late. Many die because the families didn’t have money to bring them earlier. We're seeing as families get more and more desperate”, she recalled.

UNICEF has noted a rise in “negative coping mechanisms”, where people become so desperate that they begin doing things they would not normally consider, like taking a child out of school or selling them for early marriage – sometimes babies as young as six months old.

An education for girls

Currently, Ms. Mort said that adolescent girls have not been invited back to school.

“We've got around one million high school-age girls sitting at home, denied their right to an education”, she said. “We want to see every child in school. If children are not in school, they're much more likely to be recruited by an armed group, or to fall into early marriage or to be exploited in some way”.

Even before the current Taliban rule, 70 per cent of Afghanistan’s economy was shored up by international aid.

“With that help frozen, health workers and teachers are not being paid. If you imagine a country that doesn't have a functioning education system and doesn't have a functioning health system, you'll understand how quickly it all collapses”, she explained.

Last week in a new school, the UN official spoke to a class of girls who had never had an education.

When she asked if they had a message to share with the world, a seven-year-old put her hand up and wondered if the world could keep peace in Afghanistan so that she can continue going to school.

“I just thought, God love you. It was so spontaneous, just keep peace in my country, so I can keep learning”, Ms. Mort recalled.

Newsfeed

Videos