Analysis: More storm clouds gather over Armenia, Azerbaijan

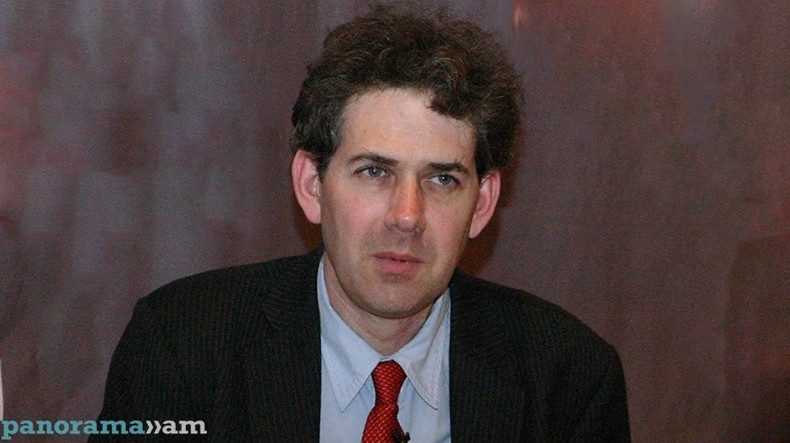

By Thomas de Waal, Carnegie Europe

In normal times, the latest upsurge in violence in the South Caucasus would have attracted a lot more attention.

Nearly 300 soldiers died in a large-scale Azerbaijani incursion into the territory of Armenia on September 13–14. Armenia says that 202 of its soldiers and five civilians died or are missing. Azerbaijan has put its losses at 80 soldiers. Let’s not forget that these are countries with small populations where these awful numbers resonate even more strongly.

A ceasefire has stopped what was by far the worst violence since the forty-four-day war of 2020 between the two countries, but Azerbaijani forces appear to be still in control of territory in border areas of Armenia.

What happened?

The fighting occurred only two weeks after a fourth round of EU-mediated high-level talks in Brussels between the two leaders, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, where progress was being made. Importantly, it followed on the heels of Russia’s military humiliation by Ukraine in the Kharkiv province.

Some media reports have misleadingly described the fighting as border clashes and made reference to the disputed territory of Nagorny Karabakh, the locus of conflict for more than thirty years. But no fighting took place in Karabakh—now a base for Russian peacekeepers—or indeed in Azerbaijani territory; it was all inside the territory of Armenia.

Azerbaijan said there were Armenian “provocations,” a claim which cannot be verified. Eyewitnesses describe heavy shelling of military targets and civilian infrastructure in, amongst other places, the village of Sotk and the resort town of Jermuk, whose civilian population was evacuated. There are credible reports of atrocities and the hideous desecration of two dead Armenian female soldiers.

Since winning an overwhelming victory in the war of 2020, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has used what a senior Azerbaijani described to me as a strategy of “coercive diplomacy” against Armenia: a mix of negotiations and force.

Having achieved most but not all of his war aims in 2020, Aliyev has new goals. The first one is compelling Armenia to sign a “peace treaty” in which it renounces claims on the Armenian-majority region of Karabakh. The second a demarcation of the Armenia-Azerbaijani border that suits Azerbaijan. The third is a new road rail and link across Armenian territory to the exclave of Nakhchivan—what it calls the Zangezur Corridor—with minimal checks and controls.

The latest round of violence is the most brutal and dangerous since 2020. It seems aimed as much against Russia as against Armenia. Russia is obliged to assist Armenia both thanks to a bilateral defense treaty and to their joint membership of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).

But Russia is also of course almost flat on its back in Ukraine. Azerbaijan looks intent on proving both that Russia is slow to support its ally and that the CSTO is a paper tiger—as its failure to act over Tajikistan’s cross-border attacks in Kyrgyzstan also demonstrates.

All this year, Armenia and Azerbaijan have been engaged in negotiations, mediated by Charles Michel, president of the European Council. The violence last week does not mean, as some commentators have asserted, that the talks were a sham or a waste of time. They had actually made a lot of progress.

The two sides agreed the substance of a deal on transportation routes earlier in the summer before the Russians raised some complications, which halted everything. Over the summer they worked intensively on texts which square an interstate treaty (Azerbaijan’s demand) with provisions for the rights and security of the Karabakh Armenians (Armenia’s demand).

The problem is one that has dogged all mediators in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict since 1991: no one pays a price for saying “no.” Condemnation for bad behavior is weak—for Azerbaijani actions last week, just as it was for egregious behavior by both sides (such as the Armenian occupation of Azerbaijani territories) prior to 2020. Leaders feel they can renounce in public what they agreed to in private, play for time, or use force.

There is also the problem of “forum shopping.” Russia is still a mediator with powerful interests, even if it is not trusted as an honest broker. Moscow has also reportedly come up with a draft peace treaty, which indefinitely postpones the issue of the status of Karabakh—a formula that the Armenians like more than the European proposal.

Simultaneously, the United States, while strongly supportive of the EU, also raised Armenian hopes by appointing a new Caucasus envoy, Phil Reeker, who is named as co-chair of the OSCE Minsk Group, the previous mediation mechanism that Yerevan favors. The blitz solidarity visit to Armenia by U.S. Congress speaker Nancy Pelosi sends more mixed messages.

The EU itself comes across as ambiguous.

In July, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen visited Baku on a mission to buy Azerbaijani gas. In her public remarks she called Azerbaijan a “reliable, trustworthy partner” and did not mention the words “peace” or “conflict” once. Azerbaijanis interpreted this as a big PR victory.

Whatever he intended or knew, this may be the moment when President Aliyev overplayed his hand. The latest fighting has undermined the domestic standing of a serious interlocutor, Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan who had committed himself to talks with both Azerbaijan and Turkey in the teeth of domestic opposition.

It has also triggered dissent inside Azerbaijan for the first time, even among some who supported the 2020 war. A pro-peace activist was sentenced to thirty days in prison. A prominent independent expert called Aliyev “maximalist” and “irredentist” and blamed him for squandering a historic opportunity to make peace with Armenia.

As funerals take place in Armenia and Azerbaijan, there will now be new efforts to get the leaders back to negotiations.

For it to have any chance of success, the Charles Michel process—currently the only viable one—needs much stronger support, from the European Commission, EU member states, and the United States. If it peters out or fails, the two dismal alternatives are that mediation again defaults to Moscow, or, worse: that the two sides get ready to fight the next war.

Newsfeed

Videos