Scientific publication of Russian Empire about Armenian village Karintak in Artsakh

In the 25th issue for the year 1898 of the project “Collection of Materials to Describe the Terrain and Tribes in the Caucasus,” V. Osipov, a teacher at Chayken school, published an article about the Armenian village Karintak.

In the early 19th century, the inhabitants of the village Khdzaberd, bordering Zangezur, were driven out by the “barbarian khans” and moved to Karintak. The inhabitants of the village were said to be prominent with braveness and strict customs and proud of their braveness. They did not want to pay tribute to the khans. Subsequently, the khan of Aliyanlu, a Kurdish tribe, fought dreadful wars against them but lost every time.

Realizing that he could not win the Khodzaburdians honestly and aware of their non-revengeful nature, the khan decided to make friends with them. He went to them, as if a as a guest, and before leaving, invited the leaders of the community to pay a return visit to him as a sign of friendship. The Khodzaburdians accepted the invitation. When they arrived at the khan’s place, he poisoned them during the meal and attacked the village. At the beginning, the inhabitants failed but they were able to drive the khan away in the end.

On another occasion, the khan decided to use the Good Friday, during which the Khodzaburdians went to church at night. When all the seniors went to church, the khan surrounded the church with numerous horsemen and exterminated everyone inside. “For three days, the river Ekhtsaget on the side of the church was flowing with blood, which gave it a new name ‘Desecrated River’ (‘Հարամ գետ’),” the legend says. Many of the villagers who had remained in the village suffered the same destiny as their fellow villagers in the church. The survivors fled leaving their property to the foe.

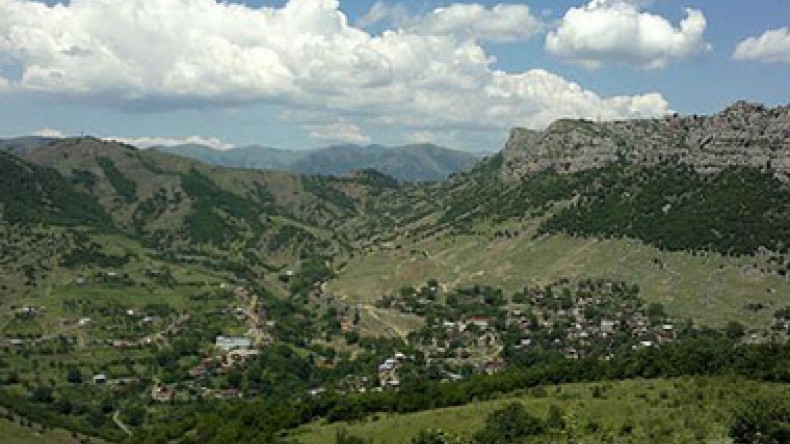

The space occupied by the village and its lands represents a basin with numerous hills and passes overgrown with bushes – the remains of the former forests with narrow and deep rocky gorges. “The branches of the Lesser Caucasus with two peaks, Big and Small Kirses right to the south of the village, surround the basin from west to south with a semicircle. A branch from Big Kirs, separated from Shushi Fortress with the river Dash Altinka, which divides those gigantic cliffs, makes another semicircle from the south to the east. The barren rocks of the Shushi Fortress, reaching almost a verst height in some places, also make a semicircle from the north,” describes the author the location of the village.

The inhabitants were mainly engaged in delivery of wood, burning calx of fine quality, husbandry, cattle breeding, horticulture and partly gardening.

Osipov points out Karintak’s “matchless hardworking” women who carried out a multitude of various works. Despite working more than men did, the women in Karintak were healthy and beautiful. They did not lose their beauty even at the old age. The author cites the local old women as saying, “When we work, we feel better. In case we sit around without having something to do, we fell unwell.”

“Indeed, she would be seen everywhere. As soon as the spring comes, she takes a piece of bread and goes to the cornfield to clear it from weeds, she works on par with her husband in the garden sowing herbs, while watering is her duty alone. In summer, as we saw above, she threshes the grain. Besides those works, she also does the domestic chores – she weaves carpets, mafrashes, kilims, saddlebags, sacks, horsecloths for donkeys, twists ropes, knits socks, sows shalwars, dresses and so on,” he writes.

Further, the author describes the original garments the Karintak women liked to wear. The headdress covered almost everything on the face but the nose and the eyes. “They hang silver or gold coins on the forehead. Almost small-nut-size silver and gold coins are hung on the cheeks. The chin is covered with a white kerchief, which is also used to close the mouth while talking to the adults. A paperboard ring covered with red or blue velvet with various ornaments on the front side is put on the head. The headdress is finished with a shawl thrown on top and a silver chain round the neck over the shawl,” describes the author. The outwear consisted of arkhalugh, which reached the knees or longer, with sleeves decorated with silver sowing and pendants, and a shirt reaching the heels. Silver coins were hung on the breast. All this was bound with red calico or silver belts. Stockings, socks and green or reddish boots constituted the footwear. It was a shame, especially for the young women, to walk barefoot.

Osipov writes that the people in Karintak were peaceful, hospitable and hardworking, but they were also rude and superstitious. “They work the whole year round. They will not sit around a minute without work. They work at night and on Sundays, too, if needed,” the author recounts noting that they lived 70 years.

The aggressive nomadic surroundings, which stole their cattle, poisoned the cornfields and mowing places during the encampment, grew in the Karitakians a great passion to the weapon, which they used to protect themselves and their fortune from the nomads.

“Sometimes a tatar neighbor would steal a Karintakian’s cattle and then come and demand baksheesh to show the place of the stolen cattle. If the villager agreed, he got his fortune back. But if he complained on the thief, the latter would certainly take revenge. That is why the villagers in Karintak prefered to agree on a peaceful deal,” the author recounts.

To be continued.

Related:

Scientific publication of Russian Empire about destruction of Christian monuments in Barda by Tatars

Scientific edition of Russian Empire: Nakhijevan was prominent Armenian city founded in C16 BC

19th century scientific edition of Russian Empire compiled historical data about ancient Erivan

Newsfeed

Videos